Earth Protect Blog

- Font size: Larger Smaller

- Hits: 3015

- 0 Comments

A World With Less Water

Water scarcity has long been a problem. But climate change, a growing global population and economic growth are putting the natural resource under even more stress.

Brown with rust two ships stand like stone upright in the yellow sand. The wind swirls salty air around the the trawlers, silence echoing across the desert-like scenery. Now part of a graveyard of ships, the boats are all that is left of the harbor at what was once the bustling fishing town of Mo’ynoq in Uzbekistan on the Aral Sea.

Since the late 1950s, the lake, once the world’s fourth largest, has been rapidly shrinking. Water that had flowed into the lake was diverted to provide irrigation for Uzbekistan’s ‘white gold’, cotton plantations spread across the arid region, while hydropower facilities and reservoirs across Central Asia have also taken their toll.

It is one of the major environmental disasters of the last half century with animal and plant life in the region dying out as a result. But it is not the only place where water has been disappearing. Bolivia’s second-largest lake, Poopó has all but vanished, with severe consequences for both wildlife and people.

“Water has already been relatively scarce,” he told DW. “It’s just that populations are growing and economies are developing, so demand for water keeps increasing, but the quantity of water that is available does not.”Scarcity of water all over the world is becoming an increasing problem. And it’s only going to get worse, said Richard Connor, editor-in-chief of the United Nation’s World Water Development Report 2016 (WWDR), released this week.

Bigger population, bigger water scarcity

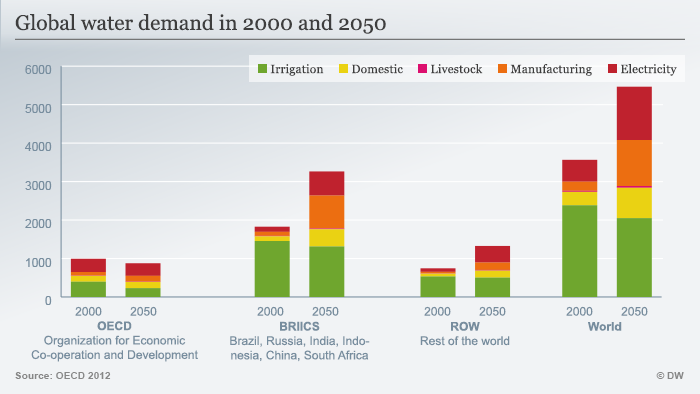

More than 70 percent of the freshwater that is taken from natural resources is used in agriculture, for food crops like wheat and rice, but also for plants like cotton. Energy production accounts for 15 percent of water usage and another 5 percent is for household usage.

But with the population expected to grow – the WWDR predicts that by 2050 there will be 9.3 billion people, 33 percent more than in 2011 – the world’s water resources are likely to come under increasing pressure.

Regions like Central Asia, the Arab world, parts of China, India and the western United States, already suffer from a physical shortage of water. But storage and infrastructure enable countries to collect water and keep it ready in times of drought.

“The magnitude will be proportional to its vulnerability,” said Connor. “Developed countries are much less vulnerable because they have the storage capacity – dams and reservoirs.”

But in the developing world, water scarcity is having the greatest impact. There are already more than 1.8 billion people, who only have access to water that is not safe for human consumption, according to the WWDR. And even in areas where there is an abundance of water, like in Sub-Saharan Africa, economic factors mean that people are not getting enough access to the natural resource.

“The water resource is there, but it doesn’t get to the fields, the factories and the cities because infrastructure and institutions are lacking there,” said Connor, adding that crops there are rain-fed because water cannot be used for irrigation. “When there is a drought, like in Ethiopia, they have serious problems that lead to food crises.”

Increasing conflict

Without improved efficiency measures, agriculture is expected to need 20 percent more water in the coming years to feed the growing population. “There are huge areas that can’t grow enough food because of water shortages,” Jonas Jägermeyr, a geographer at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Change and lead author of a paper on water management, told DW.

Meanwhile, the changing climate is expected to exacerbate the problem, with some countries becoming drier and hotter, while others experience extreme weather in the form of storms and flooding.

It is something that has already had a massive impact both economically and socially, said Connor. Three out of four jobs worldwide are dependent on water. Sectors such as agriculture, fisheries and aquaculture, and mining and resource extraction are heavily dependent on water.

It is the impact on people’s livelihoods and access to food that was partly to blame for the unrest that led to the Arab Spring and the Syrian conflict, Connor added. “I’m not saying water is the only reason for the crisis in Syria, it’s much more complicated than that, but it certainly has as much of an impact, if not more, than the actual geopolitical situation.”

Finding solutions

It is only better water management that will help deal with increasing water scarcity, according to Jägermeyr. Measures to use the water we already have for agriculture more effectively could halve the global food gap by 2050 and increase food production by 40 percent, he said in his paper.

Better irrigation techniques that don’t see water wasted through runoff from flooded fields are one way of saving the resource, he said. “There is drip irrigation, which is more high tech and could be made better with time. And in Sub-Saharan Africa they try to collect rainfall and store it in pans and cisterns to reapply when the plants need it.”

But any changes in measures would have to be introduced by individual governments and in some cases individual farmers and other stakeholders.

Meanwhile, some companies are also looking at ways to genetically modify seeds that will make crops such as sugar cane and tomatoes more tolerant to drought.

The UN has introduced ambitious targets as part of its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with aims to provide safe and affordable access to drinking water for all by 2030, to increase water-use efficiency and reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity.

It is one of the goals, Connor argues, that would have the biggest impact and also provide solutions for some of the other 17 targets ranging from dealing with hunger and poverty to education. But it will be a challenge.

“It’s going to require a much more considerable amount of investment,” said Connor. “Not just in infrastructure and operation and maintenance, but also in capacity and institutions to manage water. [But] water is the key most important thing.”

Comments

-

Please login first in order for you to submit comments