Earth Protect Blog

- Font size: Larger Smaller

- Hits: 3868

- 0 Comments

Gulf Oil Spill Anniversary: BP Disaster's Impact On Children

SOUTH PLAQUEMINES PARISH, La. -- Julie Creppel raises six children here, steps away from the lapping waves of the Gulf of Mexico. Her modest mobile home, on a narrow peninsula roughly an hour and a half south of New Orleans, puts her about as close as anyone to where, two years ago today, a BP offshore drilling operation went terribly wrong, spewing 4.9 million barrels of oil into the Gulf's constant saltwater churn.

It was the worst oil disaster in U.S. history, though for much of the nation, it remained a worrying but distant drama. Creppel says that for her and her family, the impacts were very clear and very present. The spill, she says -- and the months of efforts to stop it -- made them sick.

One son, 2-year-old Wyatt, struggles with constipation and severe skin rashes, Creppel says. Daughters Kylee and Atrea suffer massive headaches almost daily. Kasie, meanwhile, is due for an electrocardiogram for her heart palpitations. Just about everyone in the house relies on a steady supply of Nasonex nasal spray to clear their permanent congestion. Creppel counts 17 prescriptions filled for the family's ailments just last week.

“It was like a war zone,” Creppel says, recalling the squadrons of military and support planes overhead, the smoky air and the unforgiving chemical stench that characterized the summer of 2010. “When we would walk out on the porch, we couldn’t breathe. Our eyes and throats would burn.”

Creppel's complaints are not unique, and others nearby who have developed ailments share her suspicions that relentless exposure to burning oil fumes, wafting chemical dispersants and other environmental insults tied to the spill and its aftermath have compromised their health. Complaints range from the general -- confusion or persistent exhaustion -- to the specific: headaches, stomach pains, chronic, heavy coughs.

Not everyone is convinced -- and for good reason. Monitoring and research so far on the Gulf Coast has yet to make clear scientific links between health concerns and the oil spill, whether exposure to the crude oil, vapors, contaminated seafood or the chemical dispersants used to break the oil apart. A dearth of long-term studies on previous oil spills doesn’t help. Of course, the BP spill also differed from each prior disaster in terms of its magnitude, duration, emission source and an unprecedented use of dispersants and controlled burns.

“We have a piece here and a piece there, but we don’t have the whole picture put together,” says Dr. Robert Geller of Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health. “The sense I have: Many children have symptoms, but it’s unclear if the symptoms are related to the Gulf oil spill, or in spite of Gulf oil spill.”

The federal government, with several academic research institutions, is actively monitoring the health of a large number of cleanup workers and coastal residents in an effort to fill in some of the missing pieces, but findings are likely still years away.

That comes as cold comfort to residents like Creppel, who are convinced that the proof is plain in the persistent coughs and sniffles of their children.

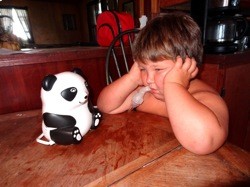

“Ethan woke up this morning not feeling good at all. He was crying. His stomach was killing him,” Creppel says of her 5-year-old son, who sits at the table shirtless and engrossed in a computer game. “He just stays sick.”

TWO YEARS LATER

For 87 days, through the spring and early summer of 2010, oil spewed from BP’s Macondo well some 5,000 feet below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico. Slicks spread across 68,000 square miles of ocean and soiled more than 1,000 miles of coastline. In addition to the estimated 210 million gallons of escaped oil, cleanup crews introduced 2 million gallons of chemicals designed to break the heavy crude into smaller globs.

South Plaquemines Parish, which includes Creppel’s town of Buras, was among the regions hardest hit by the spill, economically and environmentally. The thin strip of land trapped between the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico is accessible from New Orleans via a straight 60-mile stretch of highway. The road is flanked by oil refineries and billboards advertising legal help for oil spill damages.

On Wednesday, BP announced it had reached a settlement with more than 100,000 plaintiffs, including individuals seeking medical damage claims. Scott Dean, a BP spokesman, tells The Huffington Post that the agreement “resolves the substantial majority of legitimate claims of cleanup workers and residents of specified Gulf Coast beachfront and wetlands areas.”

The settlement covers certain chronic respiratory, eye and skin conditions that began or worsened within a couple days of exposure to the spill. Mental health issues, cancers and birth defects are among the excluded ailments, although people can still file claims for these and other unlisted medical conditions, including ones that may develop in the years ahead. The burden is on plaintiffs to prove cause and effect.

Nicole Maurer’s claims for compensation from BP have so far been “denied, denied, denied,” she says. “Did I say ‘denied?'” Her husband, William, earns a fraction of what he used to as a commercial fisherman, making their plan to move away from the Gulf Coast all but impossible. She said she hopes BP’s new blueprint for compensation will be their ticket to a healthier environment.

For now, the family remains in their trailer home just across Highway 23 from the Creppels in Buras. It’s cramped but cozy quarters with the kids home from school on this Wednesday afternoon. The three girls are lounging on a couch in the living room.

“This is their life now,” says Maurer, motioning to the girls as she opens a large kitchen cupboard that resembles a pharmacy. If they spend more than a few minutes a day outside, she says, their symptoms -- eerily similar to other South Plaquemines Parish kids -- get worse. Too often her kids don’t even feel well enough to get out the door to school, adds Maurer. Her 6-year-old daughter, Brooklyn, can’t miss any more days of school this year or she'll fail her grade. Elizabeth, 9, is just one absence behind.

But whether the Maurers’ struggle represents a broader problem in this community is less clear. Laure Rousselle, supervisor of child welfare and attendance for the Plaquemines Parish School Board, suggests she hasn’t noticed a drop in school attendance, though she says she is unable to access attendance records. Rousselle also says there’s been a push in the district over the last couple years to “make sure kids are coming to school.”

“Kids get sick,” adds Dr. John C. Carlson, medical director for the New Orleans Children’s Health Project, noting that conditions like asthma were prevalent along Louisiana's Gulf Coast before the spill due to high poverty and pollution. “It’s very difficult to tie it to any particular event.”

Again, precious little data exists.

SEE, SMELL, TASTE, TOUCH

Nicole Maurer’s husband, William, says he is “sure” he brought chemical dispersants and crude oil home every night while working on the Gulf cleanup. “I never got one piece of protective equipment or clothing,” he says, before erupting into one of his frequent coughing fits and spitting into the garbage can. A lack of protection for the cleanup crews has made its own headlines over the last two years.

Wilma Subra, a Louisiana environmental activist who won a MacArthur genius grant in 1999, said she thinks this indirect route could be responsible for children’s exposures. “Of course kids will hug their legs and jump up on their lap,” says the biochemist, who has been testing the blood of cleanup workers and other residents of the Gulf Coast and consistently finding elevated levels of toxic chemicals associated with crude oil.

More recognized are the dangers posed by breathing contaminated air, eating soiled seafood and directly touching the Gulf water and sand.

Crude oil contains some 1,000 chemicals, including cancer-causing benzene. When released into the air by high winds and high seas, some chemicals from the oil can increase ozone levels and the corresponding haze, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. These volatile organic compounds, as well as the small particles created during the controlled burning of crude oil, are notorious asthma aggravators. A two-year follow-up of children exposed to the 2007 Hebei Spirit tanker oil spill in South Korea estimated an approximate doubling of asthma in areas of high contamination, compared with low contamination.

Among the other well-known crude oil ingredients are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which can bioaccumulate in the bodies of sea life and humans, potentially causing cancer as well as reproductive and developmental problems.

With the help of the Gulf states, the EPA monitored for a range of air pollutants during the oil spill and cleanup. “These monitors did not detect levels of air pollution higher than what is normal on the Gulf coastline for that time of year,” says Alisha Johnson, an EPA spokeswoman, adding that devices continue to check air quality in selected areas along the coast.

“Monitoring and sampling data from government and private sources overwhelmingly show that cleanup workers and Gulf-area residents were not exposed to oil and/or dispersants above the levels of concern established by governmental authorities and voluntary professional organizations,” says BP’s Dean.

Critics, however, question whether the government gathered enough data to fairly declare the air safe. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon levels, for example, were not measured until the late days of the spill and many communities were left in the dark about what might be in their air from day one. The remaining monitors offer spotty coverage.

Of course, even less understood -- and therefore potentially more frightening to the residents -- are the health effects of the chemicals used to break up the oil: Corexit 9500 and 9527.

AN INCONVENIENTLY COMPLEX TRUTH

“Dispersants are an example of a huge gap in how chemicals are evaluated and used in this country,” says Miriam Rotkin-Ellman, a scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council. “We have an innocent until proven guilty system, which means that chemicals can be used in huge amounts, including in dispersants, with very little safety information. It’s just one huge experiment. The risks are really unknown.”

To date, Rotkin-Ellman says, no studies have evaluated the safety of dispersants, particularly in the manner, forms and unprecedented quantities that were used in the BP spill. One chemical involved, 2-BTE, is known to injure red blood cells, kidneys and the liver. Another, propylene glycol, is known to cause cancer in animals. The dispersants had been banned in the U.K., where BP is based, before the EPA authorized their use in the Gulf.

Another overlooked gap in knowledge: The effects of the dispersants when mixed with crude oil. Some scientists, including Bob Naman, a chemist with the Analytical Chemical Testing Lab in Mobile, Ala., say they think the mixture might magnify the toxicity of the dispersant.

Experts also speculate that these chemicals could induce ecosystem-wide changes that might prove hazardous to human health, such as an increase in toxic algal blooms or an interference in the absorption of arsenic by marine rocks coated in oil, leading to a rise in the levels of this toxin in seafood.

Regardless of any potential ongoing exposures -- huge quantities of both crude oil and dispersants still remain in the marshes and along some beaches. Dr. Carlson of the New Orleans Children’s Health Project at Tulane University suggests that initial exposures during the spill may be enough to cause long-lasting effects. For a handful of the kids he sees during the one day a week he spends in South Plaquemines Parish, he said he thinks there was something that dramatically changed at time of their exposure to the Gulf oil spill. Namely, their immune systems.

Carlson suggests that permanent damage to the immune systems can set someone up to respond inappropriately, such as with an asthma attack or severe rash, to substances in the environment that had not affected them before. Viruses and infections that would have hardly posed a challenge to their pre-exposed immune systems also begin to win more battles.

“With broken down barriers can come cascading effects,” says Carlson.

Add to that the toxic stress that can fill a household -- financial concerns, a desire to move and worry about the health problems themselves -- and the symptoms can spiral out of control. “I hate to call it psychosomatic,” adds Carlson. “But this is a very real effect.”

Dr. Michael Robichaux, an ear, nose and throat doctor and former Louisiana state senator, says that what he has seen in his Gulf coast patients over the last couple years is unlike anything he’s encountered during his 40-plus years as a doctor. “It may all sound very mumbo-jumbo, but the fact of the matter is, all these people have almost identical symptoms, from Florida to Alabama to Mississippi to Louisiana,” he says. “It’s bizarre.”

TASTES LIKE OIL

Jorey Danos of Chackbay, La., is one of Robichaux’s patients.

During the three months that Jorey spent working cleanup on the Gulf waters, his daughters Morgan, Brande and Matali would occasionally visit him in his docked boat. Now they share many of Jorey’s symptoms, which he attributes to his exposure on the water: confusion, exhaustion, headaches, stomach pains and a chronic cough.

“I get tired out of nowhere,” says Brande, 13, describing how she often needs to sit on the steps for several minutes after getting out of the shower. “I went from a straight-B student to a straight-C student this year.”

As he pulls on a pair of yellow rubber gloves, Jorey vows that his family will never again eat seafood from the Gulf. One by one, he gently plucks shrimp out of a jar by their tails: a one-eyed shrimp, a shrimp with unusual growths, a couple shrimp caked with oil. All had recently been caught from the waters off Grand Isle, La. And fisherman aren’t the only ones finding strange seafood specimens. Scientists are uncovering much the same. Test results published this week show sick and deformed fish in the vicinity of the BP well, although researchers suggest the illnesses don’t pose a threat to human health.

Julie Creppel says her family, too, will continue to abstain from seafood. They do not eat the Gulf shrimp, crabs or the fish that keep bread on their table. And based on his taste in video games, Ethan appears to be more interested in targeting land-based animals than catching seafood anyway.

“He’s got hunting on the Xbox, hunting on the PlayStation,” says Creppel. “He’s always hunting.”

Of course, steering clear of Gulf seafood is no longer a recommendation of the U.S. Food and Drug Administion. In fact, the agency has officially deemed it safe for the eating based on tests of more than 10,000 specimens.

Creppel is among the many people who lack trust in the agency’s assurances. Why, for example, did the FDA base its analysis on an average 176-pound adult? “What about Wyatt?” Creppel asks. “Wyatt is 27 pounds.”

Further, the FDA assumed that this average adult eats the equivalent of about three jumbo shrimp a week -- far less than a recent Natural Resources Defense Council survey of Gulf residents suggests. Such discrepencies led the NRDC’s Rotkin-Ellman and her colleagues to critique the new seafood standards and conclude that health risks associated with eating Gulf seafood could be as much as 10,000 times higher than that calculated by the FDA. “We’re disappointed,” Rotkin-Ellman says. “There is a large body of scientific evidence showing that they used really outdated science to do their safety assessment. We know it’s really inadequate, particularly for pregnant women and young children who eat a lot of seafood.”

Many of Creppel's relatives remain seafood eaters. She recalls the shrimp kabobs served at this year’s Easter Sunday gathering. Ethan couldn’t help but sample the tail of one, but quickly spit it out. To his mom’s embarrassment, it landed right on her leg.

Ethan looks up from his hunting game to chime in: “It tasted like oil.”

Like so many people in these parts, Creppel faces a conflict of interest. Her husband is a commercial fisherman. “Others around here are afraid to tell anyone that something is wrong because it will mess up the industry,” she says.

Her response to the push-back she receives from family and neighbors who would prefer she didn’t speak out: “If it’s killing our kids, all the money in the world isn’t going to bring our kids back.”

Comments

-

Please login first in order for you to submit comments