New research published this week reveals that vast stretches of the ocean interior abruptly lost oxygen during the transition out of the last ice age that occurred 17,000–10,000 years ago. This event was the most recent example of large-scale global warming, and was caused primarily by changes in Earth’s orbit around the sun.

Past climate events provide informative case studies for understanding what is currently happening to the modern climate system. For this research, marine sediment core records across the Pacific Ocean were used to reconstruct the subsurface “footprint” of dissolved oxygen loss during abrupt global climate warming.

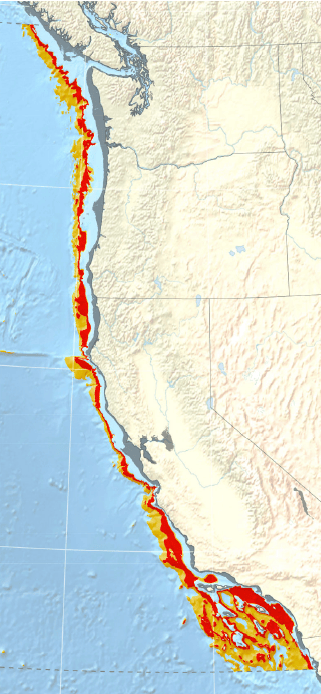

Visualization of the extent of low-oxygen seafloor at 14,000 years ago mid-way through the deglaciation. The gray shading along the coastline is the paleoshoreline, or rather where the shoreline would been when sea level was 85 meters lower than today. Red seafloor is associated with severe hypoxia and orange seafloor is associated with intermediate hypoxia.

Visualization of the extent of low-oxygen seafloor at 14,000 years ago mid-way through the deglaciation. The gray shading along the coastline is the paleoshoreline, or rather where the shoreline would been when sea level was 85 meters lower than today. Red seafloor is associated with severe hypoxia and orange seafloor is associated with intermediate hypoxia.

Like most of the life on the planet, the large majority of marine organisms need oxygen to live. Most marine life, from salmon, crabs, to shellfish, respires oxygen and many forms are intolerant of low oxygen seawater. Low oxygen zones have been incorrectly referred to as “dead zones.” In reality, they are host to bizarre ecosystems of extremophiles: worms, bacteria, and specialized urchins and bivalves colonize these harsh environments.

But, importantly, few commercially significant species of fish or shellfish can live within the low oxygen zones. So, if you are a microbial biologist you might be very excited to find a low oxygen zone, but if you are a commercial fisherperson, that low oxygen zone represents a no-go environment for fishing.

I asked Dr Tessa Hill, associate professor in the Department of Earth of Planetary Sciences at the University of California at Davis, and one of my coauthors on this research, to reflect on motivation behind this project. She said,

This study provides an excellent example of utilizing past periods environmental change to understand and predict the consequences of human-induced climate change, and where we may be headed in the future.

The new research, which I led, found that entire ocean basins can abruptly lose dissolved oxygen in sync with other global-scale climate change indicators: temperature rise, atmospheric carbon concentration increases, and sea level rise.

From the Subarctic Pacific to the Chilean margin in the Southern Hemisphere, we found evidence of extreme oxygen loss stretching from the shallow upper ocean to about 3,000 meters deep in some regions. The transition from the last ice age to today’s warmer climate substantially reduced the oxygenated habitat of the global ocean and reorganized the distribution of marine life.

Low oxygen zones were not found in the upper ocean in the glacial world; once the deglaciation (ie the shedding of massive glaciers, the rise of global temperatures) was underway, ocean systems dramatically responded. Upper ocean ecosystems, which are those that are connected to the surface ocean and have high concentrations of dissolved oxygen, were compressed towards the ocean surface. Below these oxygenated ecosystems, vast and inhospitable low oxygen zones developed.

Major changes in the distribution of oxygen are already underway in the modern ocean. Modern losses of dissolved oxygen have been detected in every ocean basin by oceanographers and modern instrumentation. I asked Dr Lisa A Levin, Distinguished Professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California at San Diego for her perspective on climate-influenced oxygen changes. She told me,

It is important that oxygen appears on our ‘radar screen’ as we look into the future, for oxygen loss in the ocean exerts critical control on the numbers, types and distributions of fish and shellfish that we harvest. By understanding the coupling in the past between the global climate system and oxygen in the ocean we are better prepared to adapt human activities to future changes in oxygenation.

Oceanographers can anticipate that subsurface low oxygen zones have the capacity to rapidly expand to states that the Earth hasn’t seen in 14,000 years. How do we manage and conserve an ocean that is moving towards a physical state that has never been observed in human history?

These are real and critical issues that modern fisheries, conservation and resource management will have to grapple with in the coming decades. The immense risk of ocean oxygen loss in a future of climate change essentially dwarfs the existing modern paradigms of ecosystem-level conservation and management action.

To reframe this information, not as a scientist, but as a citizen, a SCUBA diver and salmon eater: we really have a lot to lose in the face of climate change. We need a living, breathing ocean to sustain us, and to sustain the balance of our ocean’s biodiversity, in the future.

It is my hope that this research can illustrate the risks to our living planet and our food system, which go hand-in-hand with of the need for political solutions to human-caused climate change that are thus far lacking.